Since my most recent posting, the number of fake virus / tech support scam incidents I have been called to remedy has ballooned.

They’re persuasive: the client featured in my previous posting has since let herself be victimized by a second scammer, despite having already been burned once. (Thankfully, no damage was done to her machine this time around).

They’re persistent: one of the scams recently encountered by a client involved not just a standard un-dismissable dialog box claiming that malware was present, but also an audio file blaring a loop about how “this PC” (of course, it was a Mac) “is infected with the Zeus virus! You must call Microsoft at this number right now!” The carnival-barker behavior resumed (and locked up her browser) every time she launched Safari.

They’re opportunistic: a client signed a $400 “perpetual service contract” with a Massachusetts-based tech support company after dialing (probably misdialing) a tech support number on her Verizon bill.

They’re intrusive: the same client complained to me that, “I literally can’t turn my computer on anymore without the phone immediately ringing and some accented fellow telling me a virus has been detected on my system.”

What can you do about it?

The first rule, as we mentioned in our previous posting, is that neither Microsoft, nor Apple, nor anybody else is going to call you out of the blue and say they have detected a virus on your computer. If you get such a call, hang up.

This goes double for anyone who, after phoning you, tries to talk you into using “screen sharing” or “remote logon” software to let him onto your computer. If you let any stranger onto your computer in this fashion, it’s like handing it to him and letting him drive away — he can do anything to it he pleases.

Be careful of your typing when you type URLs into your browser bar. Through a technique known as “typosquatting,” a fraudster can set up websites that respond to these misspellings and then take advantage of your trust in the website you thought you were at. Similarly, it’s easy to follow an outdated link in a perfectly legitimate (but old) posting on the internet, only to find that the website that used to house that page is now owned by someone much less legitimate, offering phony virus warnings or fake (infected) updates of Adobe Flash to download. If you arrive at a website to find something unexpected, examine the URL bar at the top of your browser window carefully — if it doesn’t precisely match the name of the site you thought you were going to, leave immediately.

Similarly, this technique applies to phone numbers as well — you can dial a valid tech support number but use the wrong area code, and be delivered to a tech support scammer. If the support activity you are offered isn’t what you expected from your vendor, be very skeptical.

The best defense is a healthy paranoia.

Never take any caller (that you don’t already know) at face value, and don’t believe you have malware just because some intrusive (and usually illiterate) website says so.

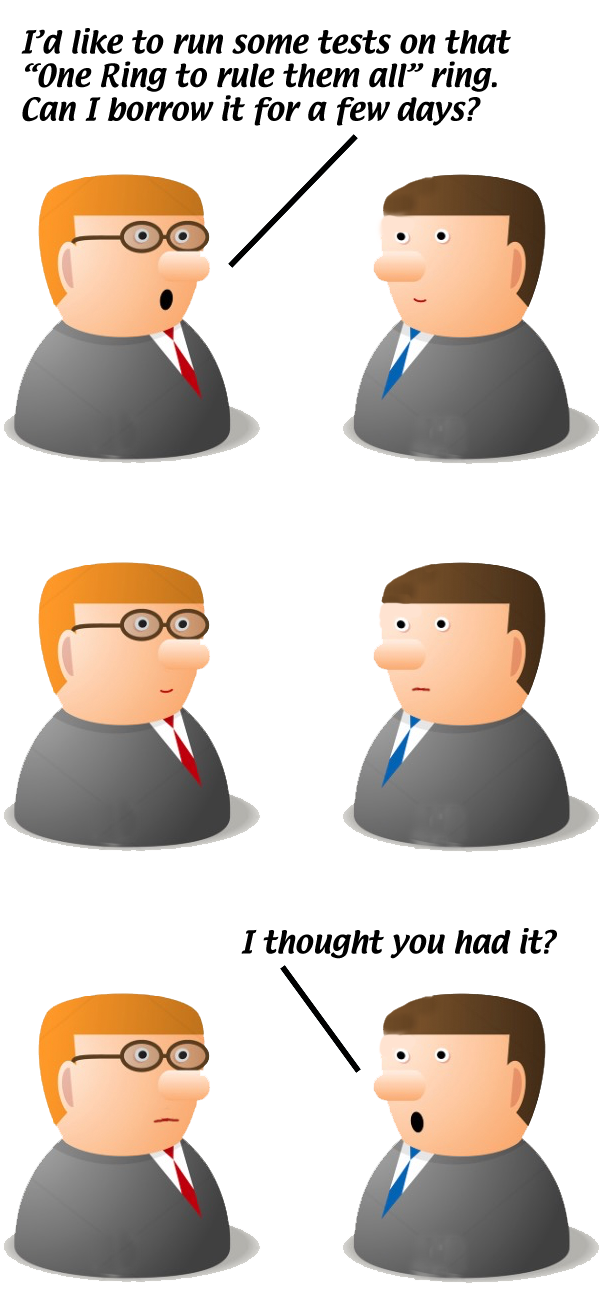

But they’ve already set the hook

The internet is a big place, and sooner or later anyone (even me) will land on a page festooned with barbs and claws, a page he wishes he hadn’t. What do you do then?

The hallmark of most browser-based malware scams is the warning box that just won’t go away. Clicking the red X (Windows close box) does nothing; trying to close the page does nothing; trying to quit the browser either doesn’t work or works only until you re-open the browser, whereupon the same warning immediately pops up.

These scams make use of JavaScript controls to disable basic operations such as back, close, and quit; and also benefit from Safari’s default behavior of re-opening the same website that was active when Safari was closed.

Though it’s tempting when faced with a dialog box you can’t dismiss, and/or an endless audio loop screaming in your ear, don’t panic. You can defeat all this.

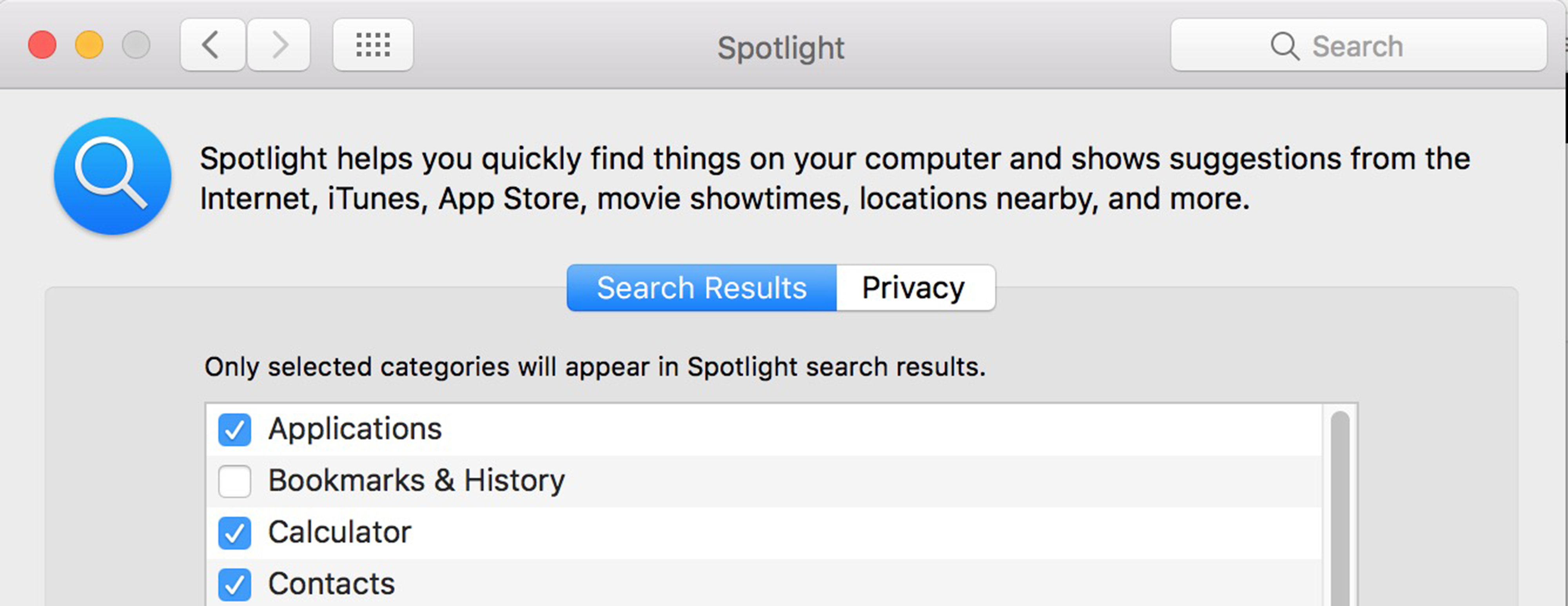

If you can’t simply quit Safari, force-quit it. Hold down the “option” key, as you click and hold on the Safari icon in the Dock, until you see a menu appear with “Force Quit,” then choose that. Alternatively, you can choose “Force Quit” in the Apple menu (or use the key combination “command-option-esc”), then select Safari.

Once you have successfully quit Safari, hold down the shift key as you click on the Safari icon in the Dock. This will defeat the “open the most recent page” feature and stop the attack from relaunching. You can examine your History if you’re curious where you ended up and how you got there, but don’t click on any part of it or you’ll end up back there.

What about the money?

If you suspect you have been duped into giving a company your credit card number to pay for phony tech support, you may be in luck. Use the web to research the name of the company you paid and/or the company that appears on your credit card bill, if different. If you see a reasonable consensus that these folks are scammers, contact your credit card company and ask for a chargeback on the grounds of fraud. You have several months to make such a complaint; the earlier, of course, the better.

If you paid for the phony service with a debit card, check, or (heaven help us) a wire transfer, this recourse is not open to you — the best you can hope for is to be able to talk the IRS into letting you deduct that amount as an “educational expense.”

If all else fails…

If after all this advice you can’t free up your machine — Mac or PC — from a malware attack — real or phony — give me a call. I can sort out the real threats from the imposters (and on the Mac side, they’re practically all imposters), and disable either kind to get you back into operation expeditiously.

I’ve come across this one on multiple client machines this month.

I’ve come across this one on multiple client machines this month.

Until recently, I’ve been using

Until recently, I’ve been using  Since I’m a fan of Monoprice’s products,

Since I’m a fan of Monoprice’s products,  When I finally got tired enough of picking my cables out of the dirt, I went hunting again. I found

When I finally got tired enough of picking my cables out of the dirt, I went hunting again. I found  In case you’re wondering whether my search ever succeeded, I eventually found

In case you’re wondering whether my search ever succeeded, I eventually found  Several times a month, various clients will ask me about setting up a new printer they have acquired. I give them all the same advice:

Several times a month, various clients will ask me about setting up a new printer they have acquired. I give them all the same advice: